The other night, I was laying in bed trying to read my phone when I started complaining to my wife about how my vision continues getting worse, how stiff I feel when I get up, and how taking too long for a recent injury to heal. “Well, yeah,” she said. “You are 44.” While attempting to see my phone while laying in bed the other night, I began to gripe to my wife about how my vision continues getting worse, how stiff I feel when I get up, and how a recent injury is taking too long to recover. She said, “Well, yeah, you’re 44.” At that point, everything starts to go south.

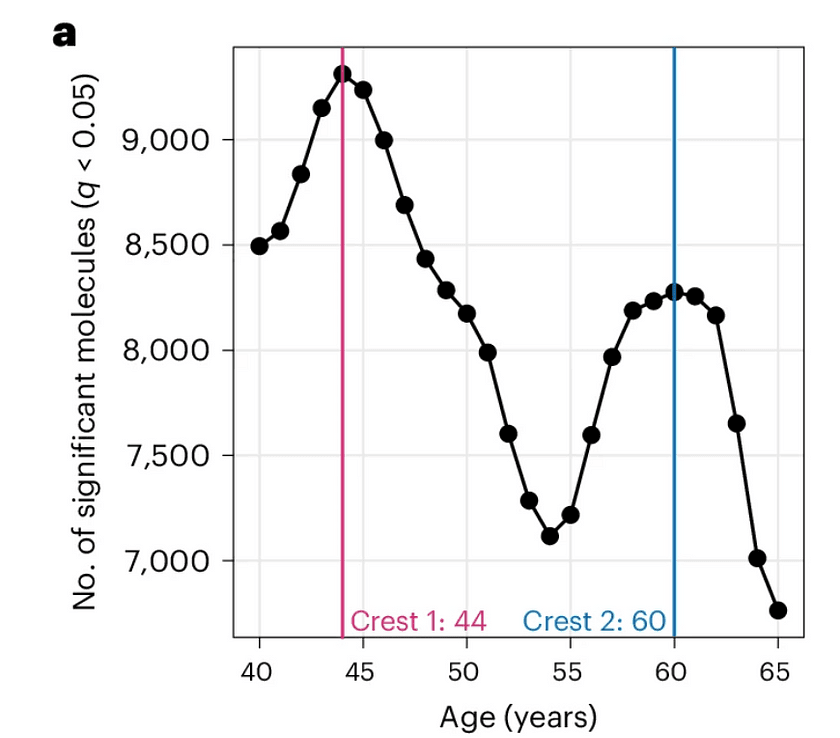

And I thought, “44? That seems really specific. I assumed that folks were complaining about 50. “No,” she said, “it’s a thing. 60 and forty-four years old. There is a drop-off location.

And what do you know? She was correct.

This study, which was published in August 2024 in Nature Aging, examined a large number of proteins and metabolites in individuals of different ages and concluded that there are significant changes in body chemistry throughout time, with the most notable alterations occurring between the ages of 44 and 60. I should be wise enough not to question my intelligent wife.

However, I secretly think that the adage “age is just a number” is true. I don’t give a damn about turning forty-four, fifty, or sixty. I am concerned about the aging of my brain and body.No matter what the calendar says, I would consider it a huge victory if I could be an 80-year-old who is content, healthy, and in complete control of his faculties.

Therefore, regardless of the number of birthdays I’ve had, I’m constantly looking for ways to measure how my body is aging. Furthermore, a recent study found that there is a very simple method for doing this.

Simply stand up on one leg.

This study, which was published in PLOS One, examined 40 people—half under 65 and half over 65—across a range of strength, balance, and gait domains, yielding some unexpected findings. The study’s idea? Strength and balance deteriorate with time, as we all know, but what deteriorates the most quickly? What may be the most accurate indicator of how our bodies are aging?

Consequently, there are several relationships between various measurements and chronological age.As a result, there are several relationships between chronological age and other measurements.

For example, this study shows a small but substantial negative association between age and grip strength, which has long been a favorite of longevity researchers.

Gripping strength decreases with aging. Overall grip strength is stronger for men (inexplicably in pink) and lower for women (inexplicably in blue). Knee strength showed somewhat weaker connections.

How about equilibrium?

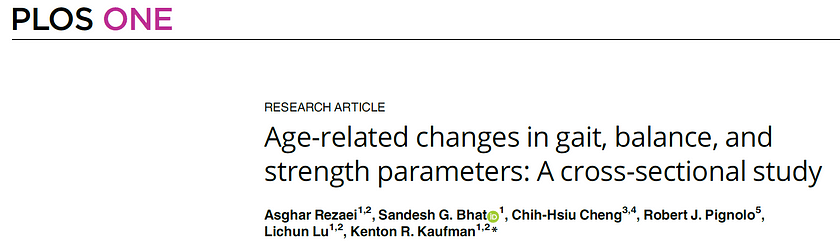

The participants were asked to stand on a pressure plate in order to gauge. They performed this with their eyes open in one circumstance and closed in another. The pressure variation around the center of the person on the plate was then measured, which essentially indicated how much the person swayed while they were standing there.

As age grew, so did sway. Additionally, sway rose somewhat greater when eyes were closed than when they were open.

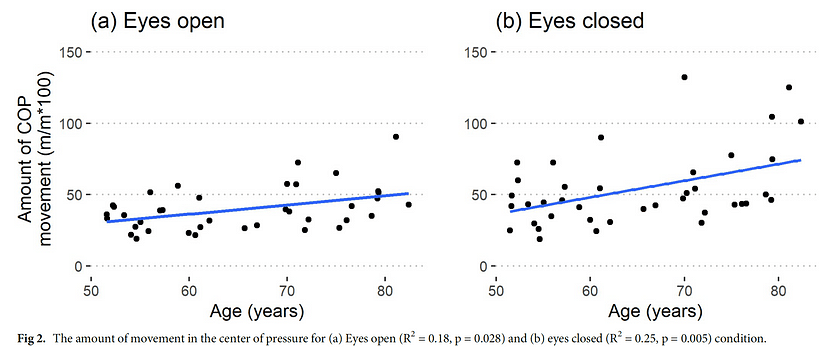

However, the most robust association between age and any of these measures was straightforward. You can stand on one leg for how long?

This shows a very sharp decline in balance time at age 65, especially for the non-dominant leg, with younger persons easily completing 10 seconds and some senior people barely reaching 2.

Naturally, I had to give this a try. And it became quite evident to me why this may be a useful metric as I stood about on one leg. In contrast to the other exams, it really incorporates strength and balance. Maintaining verticality over a relatively small basis requires unambiguous balancing. However, strength is also necessary because, well, one leg is supporting the rest of you. After some time, you do notice it.

As a possible stand-in for age-related physical deterioration, this measure, in my opinion, passes the sniff test.

However, it is important to keep in mind that this was a cross-sectional study, meaning that the researchers observed how these factors changed over time by looking at a variety of individuals at different ages rather than the same individuals.

Additionally, a linear link between age and standing-on-one foot duration is implied by the use of the correlation coefficient in graphs such as this one. I don’t think the raw data or the points on this graph are so linear. As previously said, it appears that there may be a slight decline in the mid-60s. This implies that it might not be possible to use this as a sensitive test for aging, which occurs gradually as your body ages. It’s possible that you can basically continue standing on one leg until you are unable to do so any longer. We have less notice and less time to respond as a result.

YouLastly, there is no guarantee that altering this statistic would improve your health. A competent physical therapist or physicist might probably create some workouts to extend our standing-on-one-leg times. Without a doubt, you may increase your stats significantly with practice. However, that does not imply that you are in better health. You could do better on the standardized test, but you didn’t truly understand the content. It’s similar to “teaching to the test.”

Therefore, I will not be including one-leg standing into my regular workout regimen. However, I won’t lie and tell you that I could occasionally be seen standing like a flamingo with a stopwatch in my hand, especially on my 60th birthday.

An adaptation of this commentary first appeared on Medscape.com.